Saline nature of water:

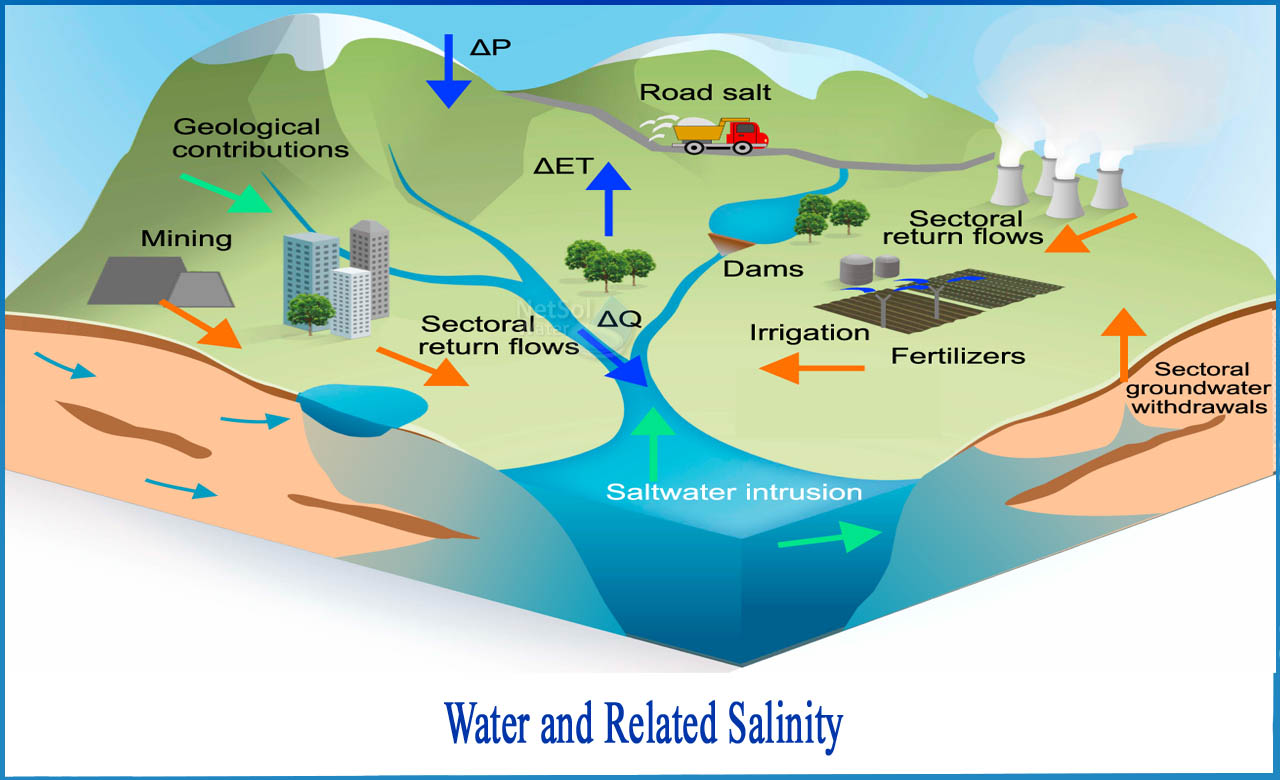

Surface water, groundwater, the flows between them, and the levels of salt they carry can all be affected by changes in landuse, seasonal variations in our weather, and longer-term climate changes.The amounts of salts in water or soils are referred to as "salinity." Primary salinity (also known as natural salinity), secondary salinity (also known as dryland salinity), and tertiary salinity are the three types of salinity (also called irrigation salinity).

You don't come into contact with saline water very often in your daily life. You're concerned about having enough freshwater to meet all of your needs. However, the majority of Earth's water, as well as practically all of the water that people have access to, is saline, or salty. Take a peek at the seas, which make up roughly 97 percent of all water on, in, and above the Earth.

Small amounts of dissolved salts in natural waterways are essential for the survival of aquatic plants and animals; increasing salinity levels modify how the water can be, but even hypersaline water can be used for some purposes. Many plants and animals, however, are harmed by excessive amounts of salinity and acidity (if present).

What is the source of the salt?

Our water resources get their salt from one of three places. To begin with, little amounts of salt (mainly sodium chloride) evaporate from ocean water and are carried in rainclouds, where they are dispersed throughout the terrain.

Second, salt released from rocks through weathering (gradual breakdown) may be found in some landscapes, and third, salt may be found in sediments left behind by retreating oceans after periods when ocean levels were much higher or the land surface was much lower.

Primary Salinity (also called natural salinity)

Natural processes such as the deposit of salt from rainfall over thousands of years or the weathering of rocks generate primary salinity.When rain falls on a landscape, some evaporates from the soil, vegetation surfaces, and water bodies, while others permeate the soil and ground water, and still others enter streams and rivers and flow into lakes or oceans. Small amounts of salt carried by rain can accumulate in soils (particularly clayey soils) over time, as well as flow into groundwater.

Large amounts of water infiltrating soils, entering and discharging from groundwater, and leaving the catchment through streams and rivers provide a flushing effect, keeping soil and groundwater salinities relatively fresh in areas where it rains a lot.

Secondary salinity, often known as dryland salinity

When groundwater levels rise, salt deposited by 'primary' salinity processes rises to the surface, causing secondary salinity. This is produced by the removal of perennial (long-lived) vegetation in drier places, i.e., areas where the soil profile and groundwater tend to collect salt over time. The amount of water lost from the landscape through plants is substantially decreased when vegetation is cleared. Instead, more water seeps into the ground, raising groundwater levels.

Increased salinity and flow in streams and wetlands are expected to raise concerns about vegetation's salt tolerance. Many plants can handle greater salinities for short periods of time, but not for extended periods of time.