- For Enquiry- 0120-2350053 || +91 9650608473 || +91 9650795306

- enquiry@netsolwater.com

How is the characterization of Water bodies done? The characterization is done by classification into three major components:

1. Hydrology

2. Physical-chemistry

3. Biology.

Water quality assessment is based on the appropriate monitoring of the above three components.

The hydrological cycle inter-connects all freshwater bodies from the atmosphere to the sea. The different stages of water ranging from rainwater to marine salt waters make the water constitute a continuum. The inland freshwaters form parts of the hydrological cycle and they appear in the form of rivers, lakes, or ground-waters.

These principal types of water bodies are closely interconnected. These forms may influence each other in a direct manner, or through intermediary stages. Each of the three forms has distinctly different hydrodynamic properties.

Rivers are primarily characterized by the unidirectional flow of current. This is accompanied by a relatively high, average flow velocity ranging from 0.1 to 1 metre per sec. The river flow is supposed to be highly variable in time, based on the climatic situation as well as the drainage pattern.

Thorough and continuous vertical mixing is achieved in rivers as a result of the prevailing currents as well as turbulence. Lateral mixing may happen only over longer distances downstream of major confluences of the water body.

Lakes are primarily characterized by a low, average current velocity of 0.001 to 0.01 metre per sec. To quantify mass movements of material, one can use water or element residence times, ranging from one month to several hundreds of years. Currents

within lakes are found to be multi-directional. Many lakes experience alternating periods of stratification as well as vertical mixing; the periodicity of which is regulated by climatic conditions as well as lake depth.

Ground-waters are primarily characterized by a rather steady flow pattern in terms of direction as well as velocity. These are largely governed by the porosity as well as the permeability of the geological material. This results in poor mixing and, based on local hydrogeological features, the ground-water dynamics can be extremely diverse.

There are multiple transitional forms of water bodies. These water bodies demonstrate features of more than one of the three basic water body types mentioned above. These water bodies are characterized by a specific combination of hydrodynamic features. The most important transitional water bodies are listed as below:

1. Seas and oceans

2. Lakes and reservoirs

3. Swamps and marshes

4. River channels

5. Soil moisture

6. Ground Water

7. Icecaps and glaciers

8. Atmospheric Water

9. Biospheric Water

10. Fluxes

11. Evaporation from oceans

12. Evaporation from land

13. Precipitation from oceans

14. Precipitation from land

15. Run-off to oceans

16. Glacial ice

Alluvial and karstic aquifers are considered to be intermediate between rivers and ground-waters. The flow regime is rather slow for alluvial and very rapid for karstic aquifers (also referred to as underground rivers).

As a result of the range of flow regimes noted above, large variations in water residence times happen in the different types of inland water bodies. The hydrodynamic characteristics for each type of water body are primarily dependent on the size of the water body as well as on the climatic conditions prevailing in the drainage basin. The hydrological regime (discharge variability) of the rivers form the governing factor for rivers.

Lakes are normally classified by their water residence time as well as their thermal regime resulting in varying stratification patterns.

Some reservoirs share many features similar to lakes. Some other reservoirs have characteristics that are specific to the origin of the reservoir. One feature that is common to most of the reservoirs is the deliberate management of the inputs and/or outputs of water for particular purposes. Ground-waters majorly depend upon their recharge regime (infiltration) through the unsaturated aquifer zone. This allows for the renewal of the ground-water body.

Reservoirs are primarily characterized by features which are intermediate between the characteristics of rivers and those of lakes. The reservoirs can range from large-scale impoundments to small dammed rivers. They have a seasonal pattern of operation and water level fluctuations.

These fluctuations are closely related to the river discharge, to entirely constructed water bodies with pumped in-flows as well as out-flows. The hydrodynamics of reservoirs are majorly influenced by their operational management regime.

Flood plains primarily constitute an intermediate state between rivers and lakes and they have a distinct seasonal variability pattern. Moreover, their hydrodynamics are determined by the river flow regime.

Marshes are primarily characterized by the dual features of lakes and phreatic aquifers. Their hydrodynamics are very complex.

The study of interconnections between inland freshwater bodies highlights the fact that these intermediate water bodies have mixed characteristics belonging to two or three of the major water bodies.

One needs to acquire a thorough knowledge of the hydrodynamic properties of a water body before the establishment of an effective water quality monitoring system. Interpretation of water quality data can provide meaningful conclusions if and only if these are based on the temporal and spatial variability of the hydrological regime.

Each freshwater body has a distinct individual pattern of physical and chemical characteristics. These characteristics are determined primarily by the climatic, geomorphological, and geochemical conditions prevailing in the drainage basin as well as the underlying aquifer.

Summary characteristics that provide a general classification of water bodies of similar nature are :

1. Total dissolved solids

2. Conductivity

3. Redox potential

The mineral content of the water body is determined by the total dissolved solids present. This is an essential feature of the quality of any water body resulting from the balance between dissolution as well as precipitation.

Oxygen content is a very vital feature of a water body since it greatly influences the solubility of metals. Oxygen content is highly essential for all forms of biological life. The chemical quality of the aquatic environment varies based on local geology, the climate, the distance from the ocean as well as the amount of soil cover, etc.

In the absence of human activities on surface waters, up to 90-99 percent of global freshwaters,(based on the variable of interest) would have natural chemical concentrations suitable for aquatic life as well as most human uses. Rare and very rare chemical conditions in freshwaters occur in salt lakes, hydrothermal waters, acid volcanic lakes, peat bogs, etc. These make the water unsuitable for human use.

However, a range of aquatic organisms has possibly adapted to these extreme environments. In different regions groundwater concentrations of total dissolved salts, arsenic and fluoride, etc., may also naturally exceed maximum allowable concentrations.

Particulate matter (PM) is a key factor in water quality, regulating adsorption cum desorption processes. This adsorption cum desorption processes depend on the following factors:

1. The quantity of PM in contact with a unit water volume

2. The type as well as character of the PM (e.g. whether organic or inorganic)

3. The contact time between the water and the PM.

The time variability of dissolved, as well as PM content in water bodies, occurs primarily from the interactions between hydro-dynamic variability, mineral solubility, PM characteristics and nature as well as the intensity of biological activity.

The development of biota (flora cum fauna) in surface waters is governed by a range of environmental conditions. These conditions determine the selection of species and the physiological performance of individual organisms. The primary production of organic matter, in the form of phytoplankton and macrophytes, is found to be most intensive in lakes and reservoirs. These are more limited in rivers.

The degradation of organic substances as well as the associated bacterial production can be a long-term process. This can be important in ground-waters as well as deep lake waters that are not directly exposed to sunlight. Whilst the chemical quality of water bodies can be measured by suitable analytical methods, the biological quality of a water body is measured by a combination of qualitative as well as quantitative characterization.

Biological monitoring can be done based on two different levels:

• The response of individual species to different kinds of changes in the environment

• The response of biological communities to different kinds of changes in the environment.

Water quality classification systems dependant upon biological characteristics have been developed for different water bodies. The chemical analysis of selected species (mussels as well as aquatic mosses) and/or selected body tissues (muscle or liver) for contaminants can be inferred as a combination of chemical as well as biological monitoring.

The biological quality which also includes the chemical analysis of biota has a much longer time dimension when compared to the chemical quality of the water. This is due to the fact that biota can be affected by chemical, and/or hydro-logical, events that may have lasted for different durations unknown before the monitoring was carried out.

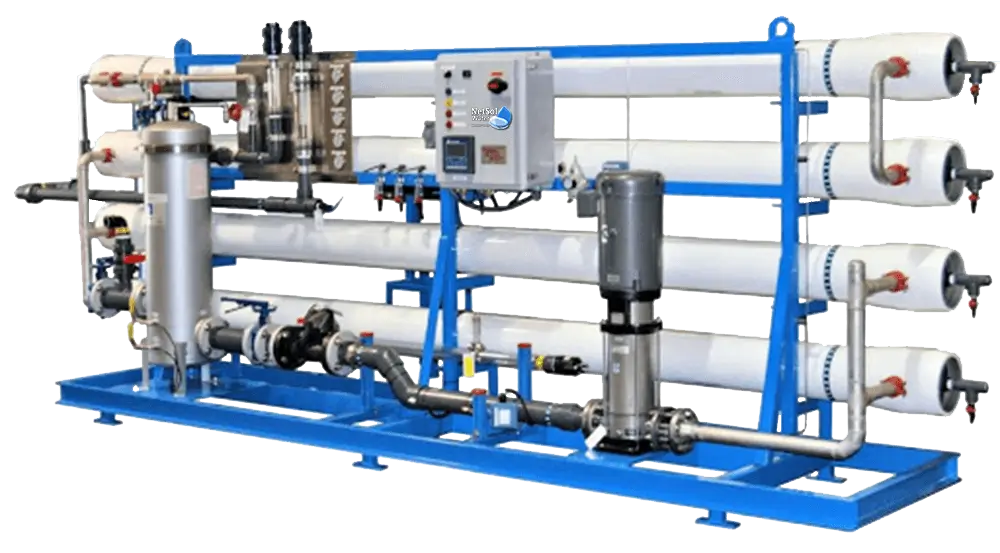

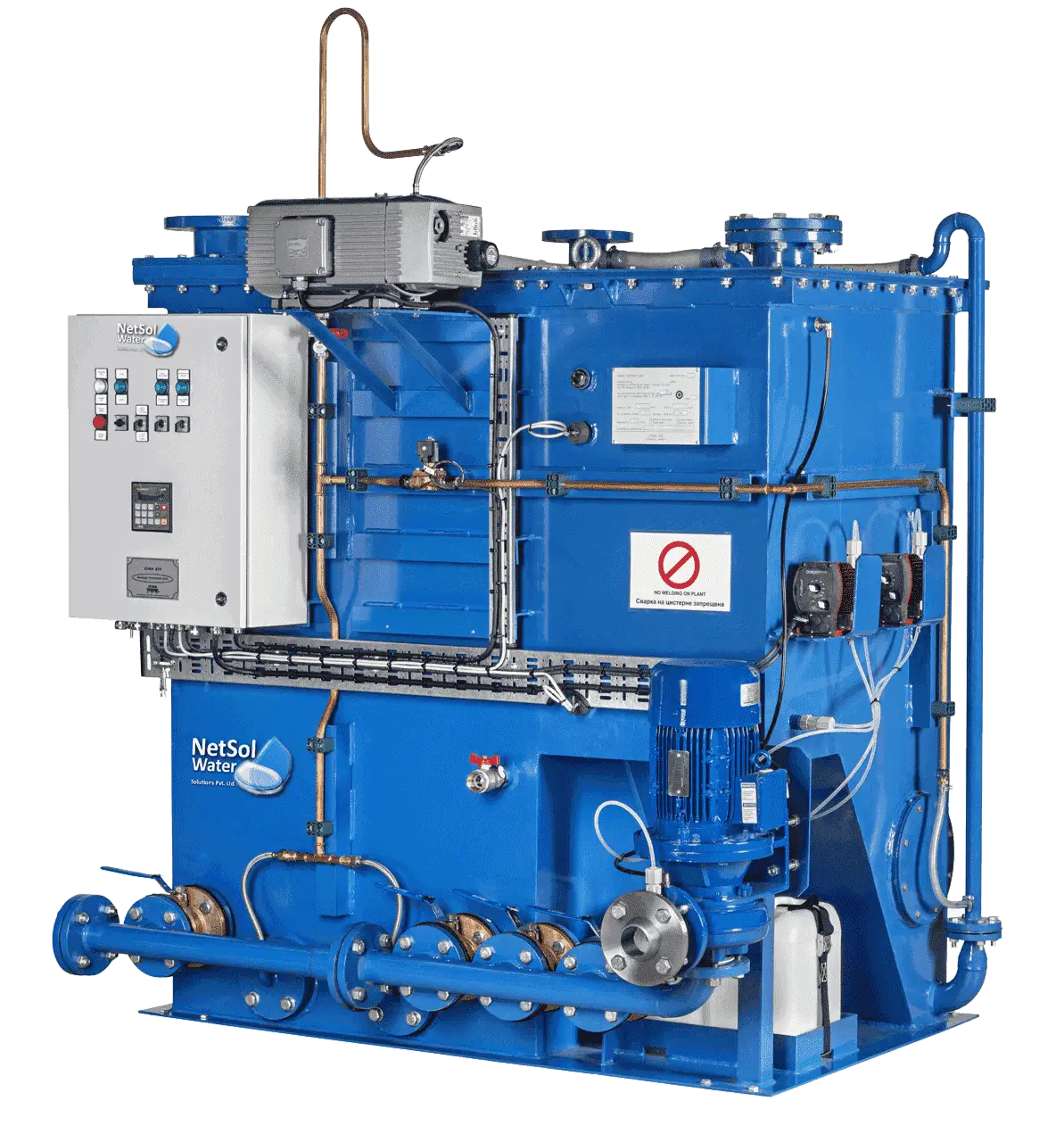

The author of the blog is associated with Netsol Water Solutions, which is into manufacturing Effluent Treatment Plant, Sewage Treatment Plant, and Water Treatment Plants.